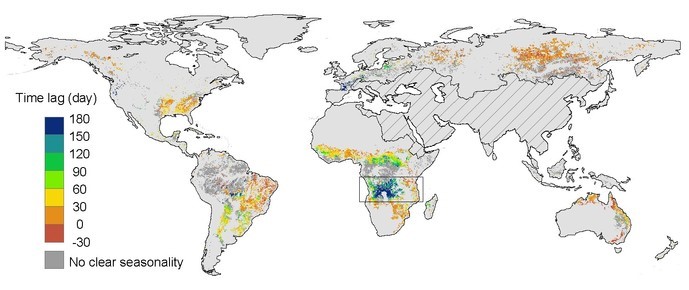

Biological cycles of a plant include many successional growth periods in which the past and the present are tightly connected. Figure shows schematic representation of the vegetation growth carryover (Source Lian et al Nat Comm 2021); image: Pixabay

The life-cycle continuity of plant growth implies that present states of vegetation growth may intrinsically affect subsequent growths, which is a type of biological memory, and can be referred to as vegetation-growth carryover (VGC). Thus, the state of ecosystems is influenced strongly by their past, and describing this carryover effect is important to accurately forecast their future behaviors. However, the processes involved in the lagged vegetation responses to precedent climate, soil, and growth conditions are highly complex and often non-linear. It should also be noted that the strength and persistence of this carryover effect on ecosystem dynamics in comparison to that of simultaneous environmental drivers are still poorly understood.

In a new study published in the journal Nature Communications authors hypothesize that the VGC has played a critical role in regulating the seasonal-to-interannual trajectory of vegetation growth. The study quantifies the impact of VGC on North Hemisphere (NH) vegetation growth with a large set of measurements, including satellite, eddy covariance (EC), and tree-ring chronologies, and compare the size of this effect against that of immediate and lagged impacts of climate change.

According to the authors, this work provides quantitative evidence that peak-to-late season vegetation productivity and greenness are primarily determined by a successful start of the growing season (via the interseasonal VGC effect), rather than by a transient or lagged response to climate. This carryover of seasonal vegetation productivity exerts strong positive impacts on seasonal vegetation growth over the Northern Hemisphere. “In particular, this VGC of early growing-season vegetation growth is even stronger than past and co-occurring climate on determining peak-to-late season vegetation growth, and is the primary contributor to the recently observed annual greening trend”, said Xu Lian and Shilong Piao from the College of Urban and Environmental Sciences, Peking University.

In order to examine whether this VGC effect operates at longer time scales of multiple years, authors performed lagged partial autocorrelations with interannual anomalies of satellite-observed NDVI and 2739 standardized tree-ring width (TRW) records. For a time lag of 1 year, a positive interannual VGC was present across northern lands, with 75.6% of vegetated areas (for NDVI) and 82.9% of the tree-ring samples (for TRW) showing positive lagged correlations. This positive interannual VGC indicates that a greener year is often followed by another greener year. When the study extended the time lags extended to 2 years, the positive correlation between current year NDVI (or TRW) and that of 2 years earlier was significant for only 14% of tree-ring samples or 5% of the total vegetated area (for NDVI). If time lags of 3 years were considered, the lagged correlation was found to be close to zero (Fig. 4a). Based on this results authors conclude that the effect of seasonal VGC persists into the subsequent year but not further.

The study also discusses process-based ecosystem models, a useful tool for predicting vegetation growth and examining the associated complex mechanisms. According to the authors, these current models greatly underestimate the VGC effect, and may therefore underestimate the CO2 sequestration potential of northern vegetation under future warming. To better simulate biological processes related to this carryover, the study highlighted that will be necessary not only using satellite and ground measurements to refine existing parameterizations, but also using leaf-level measurements to understand the physiological mechanisms controlling VGC patterns and to incorporate new process representation in model components

“Our analyses provide new insights into how vegetation changes under global warming. The VGC effect represents a key yet often underappreciated pathway through which warmer early growing season and associated earlier plant phenology subsequently enhance plant productivity in the mid-to late growing season, which can further persist into the following year”, explains Prof. Josep Penuelas from CREAF-CSIC Barcelona while he and Prof. Shilong Piao comment between them that “their results highlight the need for improved representation of the intrinsic VGC effect in dynamic vegetation models to avoid that they greatly underestimate the VGC effect, and may therefore underestimate the CO2 sequestration potential of northern vegetation under future warming.”Reference: Lian, X., Piao, S., Chen, A., Wang, K., Li, X., Buermann, W., Huntingford, C., Penuelas, J., Xu, H., Myneni, R. 2020. Seasonal biological carryover dominates northern vegetation growth. Nature Communications (2021) 12:983. Doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21223-2.